Bibliography of the Tool and the Hand

“the wheel

is an extension of the foot

the book

is an extension of the eye

clothing,

an extension of the skin,

electric circuitry,

an extension of

the

central

nervous

system”

— Marshall McLuhan

One of artist Lygia Clark's Sensorial Objects, a mobius strip binding together two hands.

“We can note how an instrumental relation

can be predicated on sympathy: to be in sympathy with the whole body is to

be useful to that body. An instrument can also thus be understood as the

loss of externality: becoming useful as becoming part. Pascal suggests that

usefulness is a form of memory: to be useful is to remember what you are

for. Not to be useful is to forget you are part of the body, to forget what

you are for. For Pascal the foot refers to human beings, who must remember they are part of God’s

kingdom. It implies we are all parts and that

as parts we must be willing to be of use or of service to the whole. But as

I explored in Willful Subjects (2014), some individuals come to be treated

as the limbs of a social body, as being for others to use (or more simply

as being for). If the workers become arms, the arms of the factory owner

are freed. If some are shaped by the requirement to be useful, others are

released from that requirement.”

— Sara Ahmed

“Digital platforms are changing the senses of reading for everyone. Our tactile learning extends to

books, smart phones, and computers. Although visual readers tend to think of reading as only visual,

reading almost always involves a combination of senses. How we make sense of the ways we read

depends on how we pay attention to our senses.”

– Touch This Page exhibition website

- Rachel Adams, Columbia University

- Kim Charlson, Perkins School for the Blind

- Georgina Kleege, University of California, Berkeley

- Catherine Kudlick, San Fransisco State University

- Robert McRuer, George Washington University

- Mara Mills, New York University

- Benjamin Reiss, Emory University

“Techniques can extend all those human aspects for which we possess a mechanical understanding, that

is, we know how it works” (1993, p. 16). These are human faculties that can be conceived of as “a

faculty, appendable by a device” (p. 16), such as our eyes, or our hands. What is not extended are

faculties that cannot be conceived of as appendable or mechanizable, which are our faculties of

judgment, morality and “the sense of place.”

— Philip Brey quoting David Rothenberg

Extended Mind Thesis 'Technology as Extension of Human Faculties.' – Philip Brey

“The first public demonstration of a mouse controlling a computer system was done by Douglas Engelbart in 1968 as part of the Mother of All Demos.”

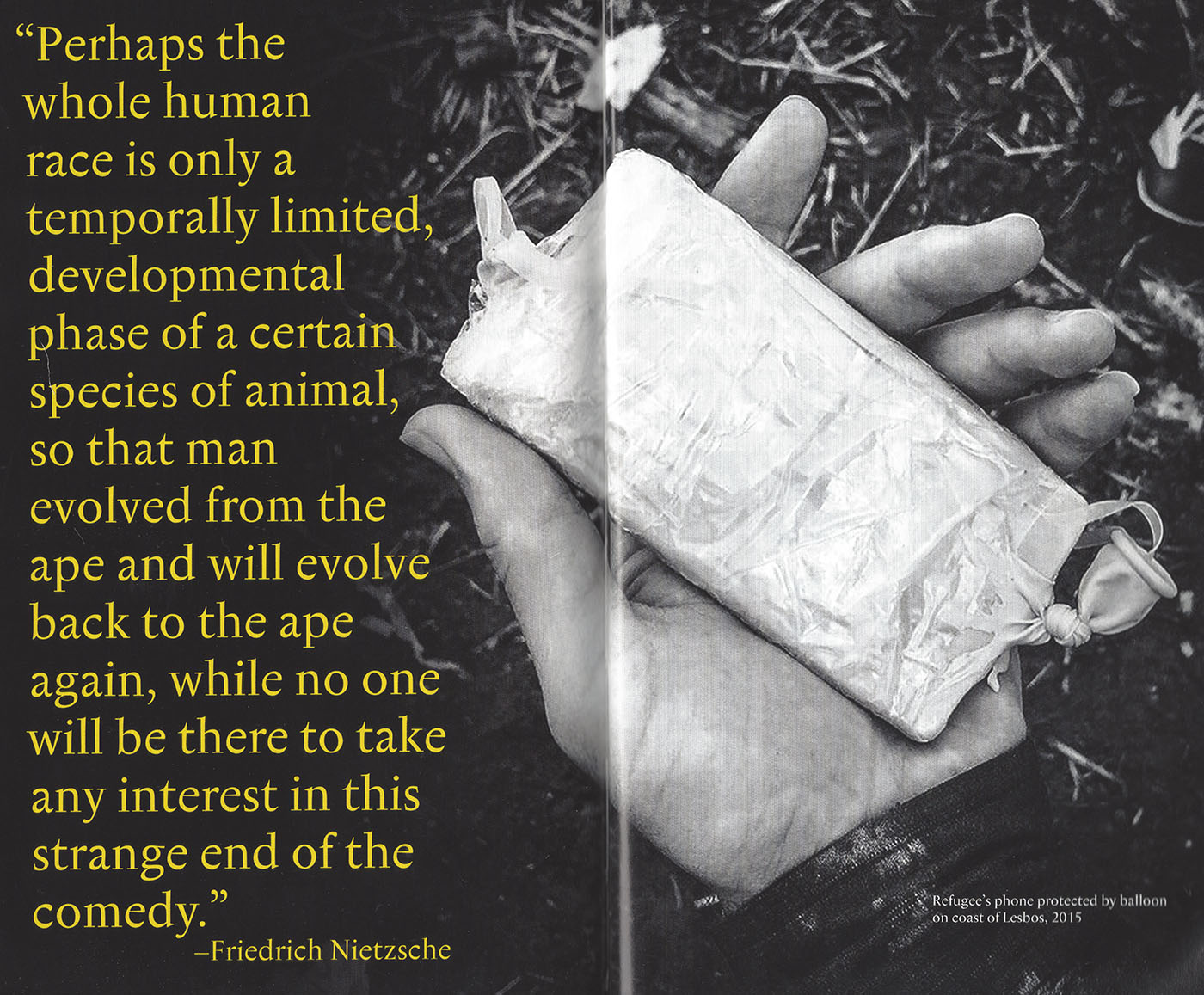

“Human biology and mentality started to radically change in 1983 with the arrival of the cell phone.

The blinking, buzzing and beeping object has become an integral part of body and brain. There are

now more active cell phones on the planet than people. Perception, social interaction, memory, and

even thought itself have become increasingly cellular. The cell phone… has taken over much of what

used to be defined as the responsibility of shelter in terms of sense of security, space,

orientation and representation. The cell phone is not simply carried, looked at, or touched or by a

person since the person is unthinkable without the device. Most people feel extreme anxiety when

they misplace their phone, lose reception, or the battery simply runs out. The cell phone has become

an integral part of the sense of self.”

– Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley

Are we human? Video from Istanbul Biennial,

2016

“This paper is an attempt to describe the nature of a new calculative background that is currently

coming into existence, a background that will both guide and constitute what counts as ‘thinking’.

It begins by providing a capsule history of how this background has become a more and more pervasive

quality of Euro-American cultures as a result of the rise of ‘qualculation’. It then moves on to

consider how this qualculative background is producing new apprehensions of space and time before

ending by considering how new kinds of sensorium may now be becoming possible. In this final

section, I illustrate my argument by considering the changing presence of the hand, co-ordinate

systems and language, thereby attempting to conjure up the lineaments of a new kind of

movement-space.”

— Nigel Thrift

Initially when

popular AI image-generator tools were introduced to the mass public, numerous articles

decried their inability to draw hands.

See also "The Uncanny Failures of A.I.-Generated Hands" by Kyle Chayka

But the same image-generators have improved rapidly. More accurately put, the software engineering power and force of capital behind AI—raw resources, channeled to it, versus other targets—are evident.

“While Parisi calls for others to develop counter-narratives, his is the story of a “progressive

mediatization of touch” (150). By the time we get to the touchscreen and the smartphone, we find

“the whole of the tactile system [reduced] to the single point of contact between finger and screen”

(275).”

— Ricky Crano, reviewing Archaeologies of Touch: Interfacing with Haptics from Electricity to

Computing by David Parisi (University of Minnesota)

Review of Archaeologies of Touch: Interfacing with Haptics from Electricity to Computing by David Parisi (University of Minnesota) by Ricky Crano

“A Hand”

A hand is not four fingers and a thumb.

Nor is it palm and knuckles,

not ligaments or the fat's yellow pillow,

not tendons, star of the wristbone, meander of veins.

A hand is not the thick thatch of its lines

with their infinite dramas,

nor what it has written,

not on the page,

not on the ecstatic body.

Nor is the hand its meadows of holding, of shaping—

not sponge of rising yeast-bread,

not rotor pin's smoothness,

not ink.

The maple's green hands do not cup

the proliferant rain.

What empties itself falls into the place that is open.

A hand turned upward holds only a single, transparent question.

Unanswerable, humming like bees, it rises, swarms, departs.

— Jane Hirshfield