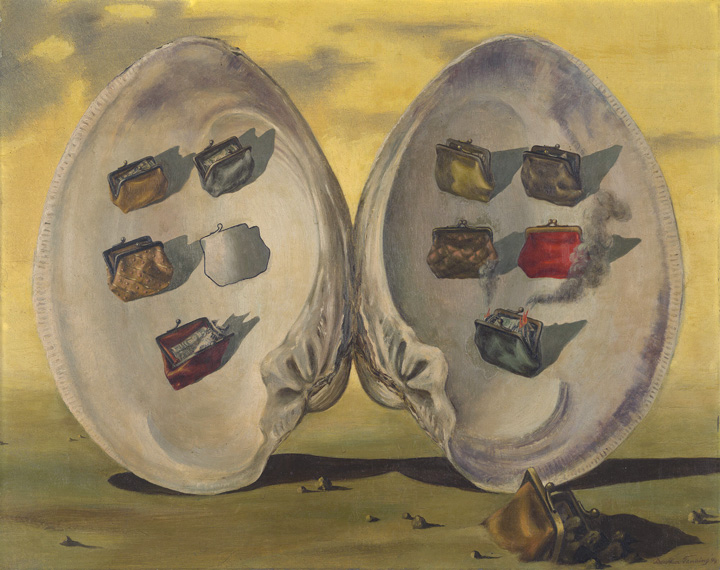

Dorothea Tanning, Rêve de Luxe (Dream of Luxury), 1944, oil on canvas, 16 x 20 in. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Gift of Thomas Fine Howard, 1955.59.4.

Archives Syllabus

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thinking about this subject has been particularly shaped by my teachers and mentors Sophie Abramowitz, Virginia Thomas, Leah Pires, Tina Campt, and Ada Smailbegovic, and their thoughtfully-constructed syllabi. I am also grateful to Kate Wells, Curator of Rhode Island Collections at the Providence Public Library, for her archival mentorship and support.

INTRODUCTION

In my junior year of college I learned how to formulate all of my ideas with the snappy, buzzy linking function of the word “as.” The body as archive. Room as archive. Building as archive. Archive of experience. Archive of feeling. Camera as gun. Archive as gun. Technology as power. Archive as technology of power. What resulted was an alluring, whirring game that I found I could quickly learn the rules to.

On the first day of my first (and only “real”) archives job, the metaphors didn’t come as quick. Staring back at my two computer monitors, they didn’t bubble up to the tip of my tongue. I was faced with the actual thing itself and its astounding materiality: shelves, offsite storage facilities, sheets of barcodes, dollies, plastic bins secured with zip ties, an array of different sizes of acid-free folders, paige boxes and Hollinger boxes and half Hollinger boxes and all their lids, spreadsheets with thousands of rows, and, and, and. Here I was. The archive as archive.

I had walked into the cavernous, light-filled reading rooms and delightfully depressing stacks armed with a bountiful smattering of theory, metaphor, and poetics. The archive as oppressive technology of power and colonialism. The archive as a space of reclamation and liberation. The archive and/as art. With my fellow undergrad classmates, I had “decolonized” the archive. [Tuck & Yang, Decolonization is Not a Metaphor] We had queered it time and time again. In fact, by the time I graduated, the archive was so unbelievably goddamn queer that it hardly resembled its previous un-queered state.

As it turns out, in the belly of the archive as archive, there arose tensions between the theory and the thing itself. This syllabus does not purport to resolve these tensions or answer any questions. That is your job, as readers. A syllabus is a thread continuously looping back on itself. This syllabus compiles a number of theoretical texts, reflections on praxis, and examples of exciting and potentially overlooked archives. I see it as an idiosyncratic “learning trail” or “curatorial trail” (1)In September, I attended a lecture and performative reading of CYBERFEMINISM INDEX by Mindy Seu at the MIT List Visual Arts Center. During her performative reading of the text, Seu used the phrases “curatorial trail” and “learning trail” to describe the series of cross-references and analog hyperlinks marked on the books pages and used to move between, across, and through entries in her indexical tome. of my personal—but collective and collaboratively-informed—encounters with archives work and archival theory. (2)As I was constructing this syllabus, I began to think of the trail as form [Some Disordered Interior Geometries], operating somewhere below structure [Sedgwick, Touching Feeling] that could be applied to the notion of the syllabus. The formulation of the syllabus as a trail emphasizes the subjective nature of the connections we form between texts, images, etc. A syllabus is just one of many possible set of moves through a series of linked objects and works. Others could and will exist. In this construction, the hand of the syllabus-creator is not hidden; their decisions to include or exclude, [Trouillot, Silencing the Past] whether conscious or not, are always active—become foregrounded. In the same way, archives are always constructed, rather than emerging naturally and neutrally (See DEFINITIONS for a slightly expanded discussion of archive as metaphor.)

> Tuck & Yang, Decolonization is not a Metaphor

“On the occasion of the inaugural issue of Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society, we want to be sure to clarify that decolonization is not a metaphor. When metaphor invades decolonization, it kills the very possibility of decolonization; it recenters whiteness, it resettles theory, it extends innocence to the settler, it entertains a settler future. Decolonize (a verb) and decolonization (a noun) cannot easily be grafted onto pre-existing discourses/frameworks, even if they are critical, even if they are anti-racist, even if they are justice frameworks. The easy absorption, adoption, and transposing of decolonization is yet another form of settler appropriation.”

> ARCHIVE AS METAPHOR

> Ada Smailbegovic, Some Disordered Interior Geometries Reanimation Library 1

Reanimation Library 2

“In his depictions of mollusks in Les parti pris the choses Ponge suggests that the slimy secretions of the snail are a kind of expression, so that an analogous relationship opens between language and the materiality of the liquids secreted by a body, or, as he elaborates in "Notes for a Seashell," language is "the true secretion common to the human mollusk." Snails can leave signs in their trails: In "Snails and Their Trails," Ng et al. suggest that males of the freshwater species Pomacea canaliculata follow mucus trails of the opposite sex, but females also follow trails laid by conspecific females. These erotic complications are also evident among the females of Littorina saxatilis, who can mask their sexual identity to avoid being pursued by males by stopping the

> Snails and their Trails, Ng et. al

Photo credit Jane Freiman

A NOTE ON GATHERING

Recently, while attending the Eastern States Exposition, or Big E, a large state(s) fair in Western Massachusetts, I was struck by a sign in the “Farm-a-Rama” barn that read “Gather an egg.” I thought it odd and funny and sweet as a directive. How can one, after all, gather just one thing? Gather seems to imply multiplicity, an act of bringing together disparate objects. Still, here I am, gathering an egg, cupping it in my hand, and offering it to you, repeatedly. I hope you enjoy some of these eggs I have gathered in my proverbial/curatorial basket.

Mindy Seu, Cyberfeminism Index

“I have long been a gatherer. In Ursula K. Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1986), Le Guin posits the first technological tool as the basket, not the spear, thereby recasting the first protagonist as a gatherer, not a hunter. Not only did this address the deeply gendered roles of these two parts, it reframed our history of technology and changed the singular hero to the plural collective, from he to we. Gathering, for Le Guin, is not a masculine, techno-utopian process of disruption or of moving, fast and breaking things, but the methodical deep labor that comes from “looking around, rather than looking ahead,” from gathering rather than hunting” (12).

> COLONIAL HISTORIES

> Ursula K. Le Guin, Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1986)

“If it is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it's useful, edible, or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people, and then later on you take it out and eat it or share it or store it up for winter in a solider container or put it in the medicine bundle or the shrine or the museum, the holy place, the area that contains what is sacred, and then next day you probably do much the same again--if to do that is human, if that's what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully, freely, gladly, for the first time.”

DEFINITIONS: WHAT IS AN ARCHIVE?

For me, it never gets easier to explain what an/the (a)(A)rchive(s) means. Part of what makes it so challenging is the multiplicity of ways in which this word is used. The Society of American Archivists proposes that “archives” is used in three ways: one refers to the records or materials themselves, which “are kept because they have continuing value to the creating agency and to other potential users;” a second usage, often written with a capital “A,” refers to the organization that preserves and manages these records; the third use might refer to the building or physical institution where the records are actually held. These definitions are helpful for grounding us in the practical dynamics of a multifaceted word, but they are also necessarily limiting, especially when it comes to talking about digital archives or non-traditional archives, the two categories that form the backbone of this syllabus.

> ARCHIVE AS METAPHOR

THEORY & PRACTICE

The following is my small—and, therefore, biased or limited—selection of texts that deal with the theory and description of both archival practice and research, including archives-informed creative practice. Many deal with critical histories of violence and oppression in the accumulation and dissemination of collections. Others propose alternative scaffoldings for building, using, and writing about archives.

Guiding Questions: What are the intersection points of theory and practice? How can theory help inform the work itself? How are collections and archives imbued with histories of violence and extraction? What strategies and modes of being can we employ to account for, resist, and remake these conditions?

Overholt, “Five Theses on the

Future of Special Collections”

“We are privileged to be working at the dawn of an era in

which special collections will become the raw materials upon which the creative energies of the

world can be exercised. Once freed from the confines of the reading room and transmuted into

malleable digital form, we can expect an explosion of innovative uses by non-traditional users.

Indeed, that process is already beginning.” (18)

Christen & Anderson, “Toward Slow Archives”

“The long arc of collecting is not just rooted in colonial paradigms; it relies on and continually

remakes those structures of injustice through the seemingly benign practices and processes of the

profession. Our emphasis is on one mode of decolonizing processes that insist on a different

temporal framework: the slow archives. Slowing down creates a necessary space for emphasizing how

knowledge is produced, circulated, and exchanged through a series of relationships. Slowing down is

about focusing differently, listening carefully, and acting ethically. It opens the possibility of

seeing the intricate web of relationships formed and forged through attention to collaborative

curation processes that do not default to normative structures of attribution, access, or scale.”

(87)

Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives (Le goût de

l'archive)

“In the archives, whispers ripple across the surface of silence, eyes glaze over, and history is

decided. Knowledge and uncertainty are ordered through an exacting ritual in which the order of the

note cards, the strictness of the archivists, and the smell of the manuscripts are trail markers in

this world where you are always a beginner. Beyond the absurd rules of operation, there is the

archive itself. This is where our work begins” (52)

“According to archival lore, one veteran of the archives, striving to stave off boredom., slipped a ring on each of her fingers, just to be able to watch the light play on them as her hands flipped through these endless tall pages over and over again. She hoped by this means to keep alert when consulting these documents that, while undeniably opaque, are never silent” (13)

> OPACITY

Susan Howe, Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of the

Archives

“Quotations are skeins or collected knots. ‘KNOT, (n. not…) The complication of threads made by

knitting; a tie, a union of cords by interweaving; as, a knot difficult to be untied. Quotations are

lines or passages taken at hazard from pile up cultural treasures. A quotation, cut, or loosely

teased out as if with a needle, can interrupt the continuous flow of a poem, a tapestry, a picture,

an essay; or a piece of writing like this one. ‘STITCH, n. A single pass of a needle in sewing.’”

(31)

> A NOTE ON GATHERING

Kara Keeling, “Looking for M—”

“…[T]he past is put in the service of the present. It is a sort of “making visible” in the present

what had been hidden through the struggle for hegemony in the past.”

> OPACITY

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Schweitzer and Henry, “Afterlives of Indigenous

Archives”

“As Vizenor produces a palimpsest of songs and stories in Summer in the Spring, he also moves

tribal, cultural resources into a constellation of realized material re-curations. The palimpsest

operates as a re-curation of material resources that were previously collected, selected, held in

different spatial and formal contexts, and arranged therein for different uses, under different

interpretive terms of distribution and possession, legal and otherwise.”

> COLONIAL HISTORIES

Tina Campt, Listening to Images

“It strives for the tense of possibility that grammarians refer to as the future real conditional or

that which will have had to happen. The grammar of black feminist futurity is a performance of a

future that hasn’t yet happened but must. It is an attachment to a belief in what should be true,

which impels us to realize that aspiration. It is the power to imagine beyond current fact and to

envision that which is not, but must be. It’s a politics of pre- figuration that involves living the

future now—as imperative rather than subjunctive—as a striving for the future you want to see, right

now, in the present.” (17)

> OPACITY

Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire

“The repertoire requires presence: people participate in the production and reproduction of

knowledge by ‘‘being there,’’ being a part of the transmission. As opposed to the supposedly stable

objects in the archive, the actions that are the repertoire do not remain the same. The repertoire

both keeps and transforms choreographies of meaning.” (20)

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”

“Narrative restraint, the refusal to fill in the gaps and provide closure, is a requirement of this

method, as is the imperative to respect black noise—the shrieks, the moans, the nonsense, and the

opacity, which are always in excess of legibility and of the law...”

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

“Wayward: to wander, to be unmoored, adrift, rambling, roving, cruising, strolling, and seeking. To

claim the right to opacity. To strike, to riot, to refuse.” (277)

> OPACITY

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Donna Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy”

“I want to show the reader how the experience of the diorama grew from the safari in specific times

and places, how the camera and the gun together are the conduits for the spiritual commerce of man

and nature, how biography is woven into and from a social and political tissue” (249).

> COLONIAL HISTORIES

Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and

and Lesbian Public Cultures

“My materials emerge out of cultural spaces—including activist groups, women’s music festivals, sex

toy stores, and performance events—that are built around sex, feelings, and trauma. These publics

are hard to archive because they are lived experiences, and the cultural traces that they leave are

frequently inadequate to the task of documentation. Even finding names for this other culture as a

‘way of life’—subcultures, publics, counterpublics—is difficult. Their lack of a conventional

archive so often makes them seem not to exist, and this book tries to redress that problem by

ranging across a wide variety of genres and materials in order to make not just texts but whole

cultures visible.” (9)

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

> Ann Cvetkovich: Artist Curation as Queer Archival Practice

Bad Archives

“The bad archive forms itself in alternative spaces, gathering ordinary scraps together in one

place, working independently from the traditional archive and its history of oppression, working

against those practices by being outside them.”

“These are ephemeral acts and public gestures, during crisis, that tell the story and spread the word, working across time, within and against erasure. Finding and learning about them is rewarding work. Sharing them is our responsibility.”

“And so I’d like to speak about what I’m calling non-cooperative archival practices. Non-cooperative because these are the gestures that emerge out of urgent times, as acts of resistance. These are archival impulses that have nothing to do with the conventional archive, or archival studies. These are the informal, independent, wild, failed archives, bad archives, that form lovingly and messily in basements, in closets, in storerooms, in parks, dead-end hand-coded web pages, and YouTube playlists. Unsearchable archives, improperly cared for, radically open and accessible collections that don’t really protect what they keep. These were never even archives at all.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

> OPACITY

> Video Remains: Nostalgia, Technology, and Queer Archive Activism

“Video Remains practices a queer archive activism in its reliance upon the recorded personal stories of regular people played out largely in respectful real time. But as significantly, the tape enacts a queer practice by commingling history and politics with feelings, feelings of desire, love, hope, or despair for both my videotape evidence and my anticipated audience.” (326)

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

José Esteban Muñoz, Ephemera as Evidence: introductory Notes to Queer Acts

“Queerness is often transmitted covertly. This has everything to do with the fact that leaving too much of a trace has often meant that the queer subject has left herself open for attack. Instead of being clearly available as visible evidence, queerness has instead existed as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments, and performances that are meant to be interacted with by those within its epistemological sphere—while evaporating at the touch of those who would eliminate queer possibility” (6)

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

Ours is a dense moment for archives work. Digitization practices and born-digital collections have radically altered the terrain of special collections, with profound possibilities for sharing and circulating materials that have previously only been seen and touched in imposing marble buildings and echo-y reading rooms. The sources gathered here are examples of digital archives in action. Many of them challenge the very notion of what an archive is and what it can do.

Guiding Questions: How has the digital expanded the limits of what we consider to be an archive? How are digitized and born-digital archival materials circulated differently from traditional archives? What are the possibilities and limitations of such ease of dissemination?

McKinney, Feminist Digitization Practices at the Lesbian Herstory Archives

“Completing the digitization of this collection may not be possible, but the LHA [Lesbian Herstory Archives] is doing it anyway, following the same kind of philosophically utopian but technologically pragmatic feminist media politics that guided the oral history movement that created these tapes in the first place. Any digitization project, with its big promises of preservation and access, can only ever be a partial gesture or “attempt” in practice.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

WEB ARCHIVES

Artexte

(online projects + exhibitions)

(digital repository)

(library + exhibition space)

Digital Transgender Archive

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Internet Archive

Queering the Map

> MAPPING

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Documents d’artistes

Nakba Archive

> COLONIAL HISTORIES

South Asian American Digital Archive

> COMMUNITY ARCHIVES

Black Trans Archive

> OPACITY

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Europeana

JvE Library: Archiving the Present

> Archival Consciousness

INSTAGRAM ARCHIVES

Black Archives

Latinx Family Photo Archives

Veteranas and Rucas

Asian Cinema Archive

COMMUNITY ARCHIVES

Ours is a dense moment for archives work. Digitization practices and born-digital collections have radically altered the terrain of special collections, with profound possibilities for sharing and circulating materials that have previously only been seen and touched in imposing marble buildings and echo-y reading rooms. The sources gathered here are examples of digital archives in action. Many of them challenge the very notion of what an archive is and what it can do.

Guiding Questions: How has the digital expanded the limits of what we consider to be an archive? How are digitized and born-digital archival materials circulated differently from traditional archives? What are the possibilities and limitations of such ease of dissemination?

Lisa Darms, “Archives Often Aren’t in the Hands of Their Own Communities. Here’s Why We Need to Support

Self-Sustaining Models” > Women’s Studio Workshop

“My generation of activist archivists inherited responsibility for collections that had been formed

by decades of racist and sexist collecting policies creating histories that were heavily skewed

towards stories of “great white men.” Our antidote was to “fill the gaps,” seeking to form new

canons and creating collecting areas that brought the overlooked and the marginalized into

mainstream collections. We also sought to prioritize ethics of care, foregrounding professional

humility and a commitment to service. This meant insisting on mutual consent and self-determination

in the donation process. … At the same time, some people in my community were asking why the

collection couldn’t be formed in the towns where the scene had begun. Why did their archives have to

be ingested into mainstream institutions, replicating the cycles of commodification and

objectification that the movement had been formed to subvert?”

> Women’s Studio Workshop https://wsworkshop.org/

EXAMPLES

PPL Community Archives

“What are community archives? They are collections of materials - in all sorts of formats - that are

created by people and community groups to document their shared experiences, art and activism,

cultural history, identity and heritage. Community archives are created by and for the groups that

they represent.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Queer.Archive.Work

“Queer.Archive.Work, Inc. (QAW) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) library, publishing studio, and residency

serving Providence, RI and beyond. … QAW aims to be accountable, to center marginalized voices

through intersectional work, and to cultivate anti-racist, safe platforms for independent, queer

publishing.”

> Bad Archives

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Interference Archive

“The mission of Interference Archive is to explore the relationship between cultural production and

social movements. This work manifests in an open stacks archival collection, publications, a study

center, and public programs including exhibitions, workshops, talks, and screenings, all of which

encourage critical and creative engagement with the rich history of social movements.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Interference Archive

“The Visual AIDS Archive and Artist Registry collects personal papers and records pertaining to the

lives and work of artists living with HIV and AIDS, as well as those who have passed. The archive

was started in 1994 by Frank Moore and David Hirsh as a response to losing not only friends in the

AIDS crisis but also the loss of art and personal papers that often followed.”

Lesbian Herstory Archives

“The Lesbian Herstory Archives exists to gather, preserve and provide access to records of Lesbian lives and activities. Doing this also serves to uncover and document our herstory previously denied to us by patriarchal historians in the interests of the culture that they served. The existence of the Archives will thus enable current and future generations to analyze and reevaluate the Lesbian experience.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Visual AIDS Archive

“The Visual AIDS Archive and Artist Registry collects personal papers and records pertaining to the lives and work of artists living with HIV and AIDS, as well as those who have passed. The archive was started in 1994 by Frank Moore and David Hirsh as a response to losing not only friends in the AIDS crisis but also the loss of art and personal papers that often followed.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Texas After Violence Project

“Texas After Violence Project is a public memory archive that fosters deeper understandings of the

impacts of state violence. Our mission is to help build power with directly impacted communities,

centering their dignity, agency, and expertise to cultivate restorative and transformative justice.

Our vision is a culture of care that addresses and prevents violence without compounding harm and

trauma. A culture that centers the needs of victims, survivors, and their loved ones through

community-based accountability and healing. Where family and community relationships that have been

torn apart by the carceral state have been mended.”

> COLONIAL HISTORIES

UCLA Community Archives Lab

“What are community archives? Community archives are independent memory organizations emerging from

and coalescing around vulnerable communities, past and present.”

History Pin

“Historypin is a place for people to share photos and stories, telling the histories of their local

communities.”

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

> MAPPING

The People’s Graphic Design Archive

“The Archive is for Everyone!”

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

Black Baltimore Digital Database

“A digital home for your history, your legacy and you.”

> ARCHIVES AND THE DIGITAL

Invasive Queer Kudzu

“Invasive, a project for Southern queers and their allies, subverts the negative characterization of invasive species and uses queer kudzu as a symbol of visibility, strength and tenacity in the face of presumed “unwantedness”.”

> QUEER & TRANS HISTORIES

Boston Research Center > Boston Public Library Community History and Digitization Project

Franklin Furnace Archives

“Franklin Furnace’s mission is to present, preserve, interpret, educate, and advocate on behalf of avant-garde art, especially forms that may be vulnerable due to institutional neglect, cultural bias, ephemerality, or politically unpopular content.”

Boo-Hooray

“Boo-Hooray is dedicated to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of 20th and 21st century cultural movements.”